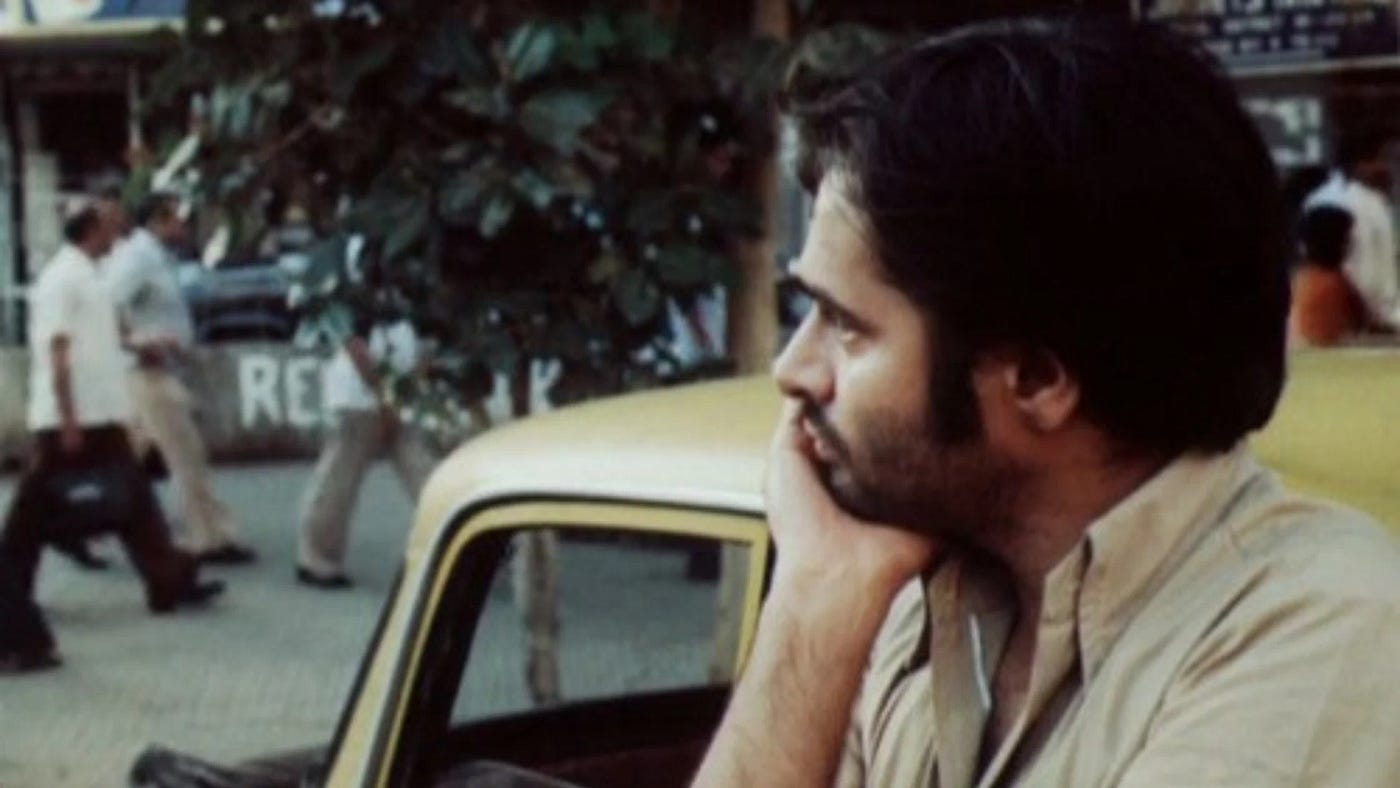

One of the most soul-stirring songs to come out of Indian cinema is from a relatively under-regarded film called (1978, Dir: Muzaffar Ali). In the film, Farooq Sheikh’s character is an urban migrant who has moved to the city of Bombay (as it was called back then) to find work after his land was usurped. He has left behind his family, and hopes to make enough money to return to them and continue his familiar life. But once in the city, he struggles and finds himself alienated; the great modern affliction of humankind. But before I get to the song, a little philosophy is in order.

It has generally been accepted throughout human history (from the time that homo sapiens became more self-aware than other beasts) that to be human means to have certain essentially human qualities and drives. These were not the same as the essence of other beasts, to say nothing of the essence of non-living objects.

Plato’s theory of forms delivers this message when he says that a table has a certain essence which we may consider its tableness, as it were. We know when we see a table that that is what it is, just as we know when it is not. Similarly, one might look at a lion and say that its essence is to be majestic and kingly, but a fox’s essence may be to be shrewd and deceptive.

For humans, self-aggrandising as we are, this essence was godly. After all, we were made in God’s image (never mind that it’s actually the other way around), so we must be more than mere beasts walking the earth. We are semi-divine creatures, rightly enslaving everything else on this planet that has been created for our use, and we commune directly with God until we return to Him (God is obviously male).

The change we find in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, rife with new knowledge (evolution, rationalism) and great conflicts, is a cataclysmic crack in our self-understanding. Our exploitative systems of power, our shock at each other’s savagery, and our disenchantment with centuries-old traditions, along with the rise of individualism and human rights, cut our moorings. No longer could an individual be sure of one’s own essence.

“Am I the exploited or exploiter? Am I just or unjust? Do I support my family or does my family support me? Am I a good member of my community even if I disagree with it? Must I stand by in faith while allowing bloodshed? Must I run the race everyone else is running?” These, and more questions could run through the minds of uprooted individuals every day.

And with the kind of human migrations witnessed during these centuries (because of war or economics), more and more people had to start thinking all over again. Purpose had become elusive, and so had identity. To use Jean-Paul Sartre’s magnificent and pithy phrase, “Existence precedes essence,” implying that we can no longer merely accept that we are creatures with a pre-set essence. We needed to find our own.

We return to our despondent taxi driver, Ghulam Hasan (Sheikh’s character), in an alien city. With Seene mein jalan, aankhon mein toofan (lyrics by Shahryar, music by Jaidev, sung by Suresh Wadkar) playing in the background, we see him driving his taxi through the city, passing throngs of people. Noticeably, there is never a passenger, and Ghulam is always alone with his thoughts. His expression is detached, pained, and typical of one who cannot see the end of the road, only what’s right in front of him.

The lyrics go thus:

Seene mein jalan, aankhon mein toofan sa kyun hai

Why is there burning in my chest, storm in my eyes?

Is shehar mein har shaks pareshaan sa kyun hai?

Why is every individual in this city troubled?

Dil hai toh dhadakne ka bahaana koi dhoonde.

Since we have a heart, we look for an excuse for it to beat.

Patthar ki tarah behis-o bejaan sa kyun hai?

Why then is it senseless and lifeless like stone?

Tanhaai ki ye kaun si manzil hai, rafiqon?

Which road of loneliness is this, my friends?

Taa hadd-e-nazar ek bayaban sa kyun hai?

Why is it like a desert as far as the eyes can see?

Kya koi nayi baat nazar aati hai hum me?

Do you notice anything new in me?

Aaina hamein dekh ke hairan sa kyun hai?

Why is even the mirror puzzled looking at me?

Removed from his place of birth, from the home he shared with his family, Ghulam is adrift in the city. His friend, who has been there longer than him, is struggling to marry the woman he loves. They cannot afford a home, no matter how hard they work. And there is never enough money collected that will allow Ghulam to return home with his mission fulfilled. He is stuck in a rut, in a state of monotony that repeats like Groundhog Day. And it is not just them but every individual, every shaks, who is troubled. Nobody is inheriting peace or stability. They each have to seek it, find it. Their reflections betray them because there is no image to be recognised anymore, because we have all gotten cut off from what we felt we knew.

The most existential line in the song then is, Dil hai toh dhadakne ka bahana koi dhoonde. When we are pushed into this life and into circumstances that are beyond our control, when there is no destination in sight, what reason for existing can one find? For what purpose will the heart beat? Existence precedes essence, after all.

Perhaps Shahryar wasn’t thinking of Sartre when he wrote this, but the existential dilemma can be shared by people across time and space. It is when you are lost in your own search that, suddenly, lines like this can express your unpronounced turmoil. Perhaps Sartre would have loved this line as much as I do. It is the sound of that searching heart’s beat.

Originally published at https://indigenousweb.com

Leave a Reply