Khwaja Ahmad Abbas (1914–1987) was, in more ways than one, at the beating heart of the Hindi film industry during what some may call its golden era. He had worked as a writer, and then as a director. But a new book, or rather, a new translation of one of his books, has re-introduced his primordial cinema avatar — film critic.

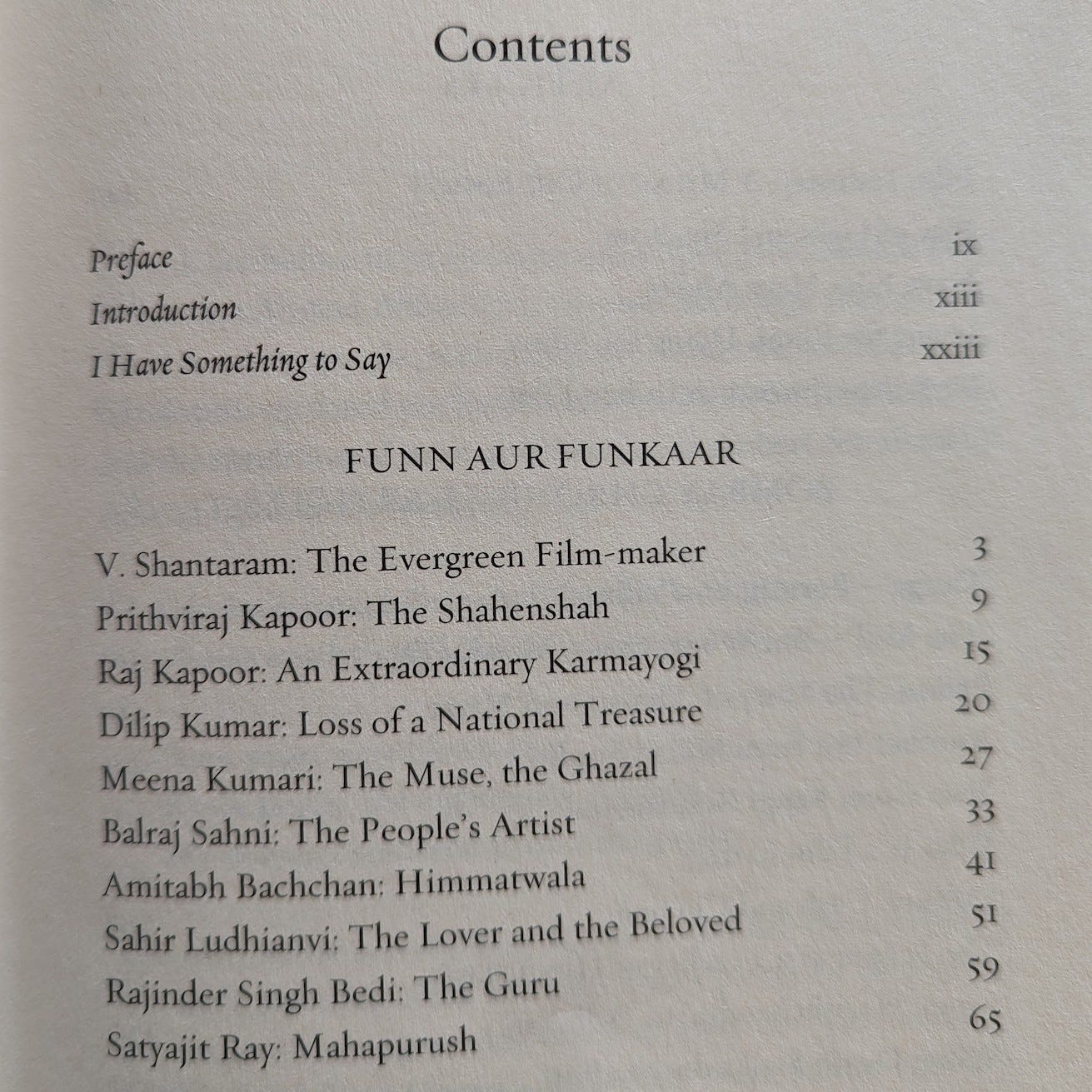

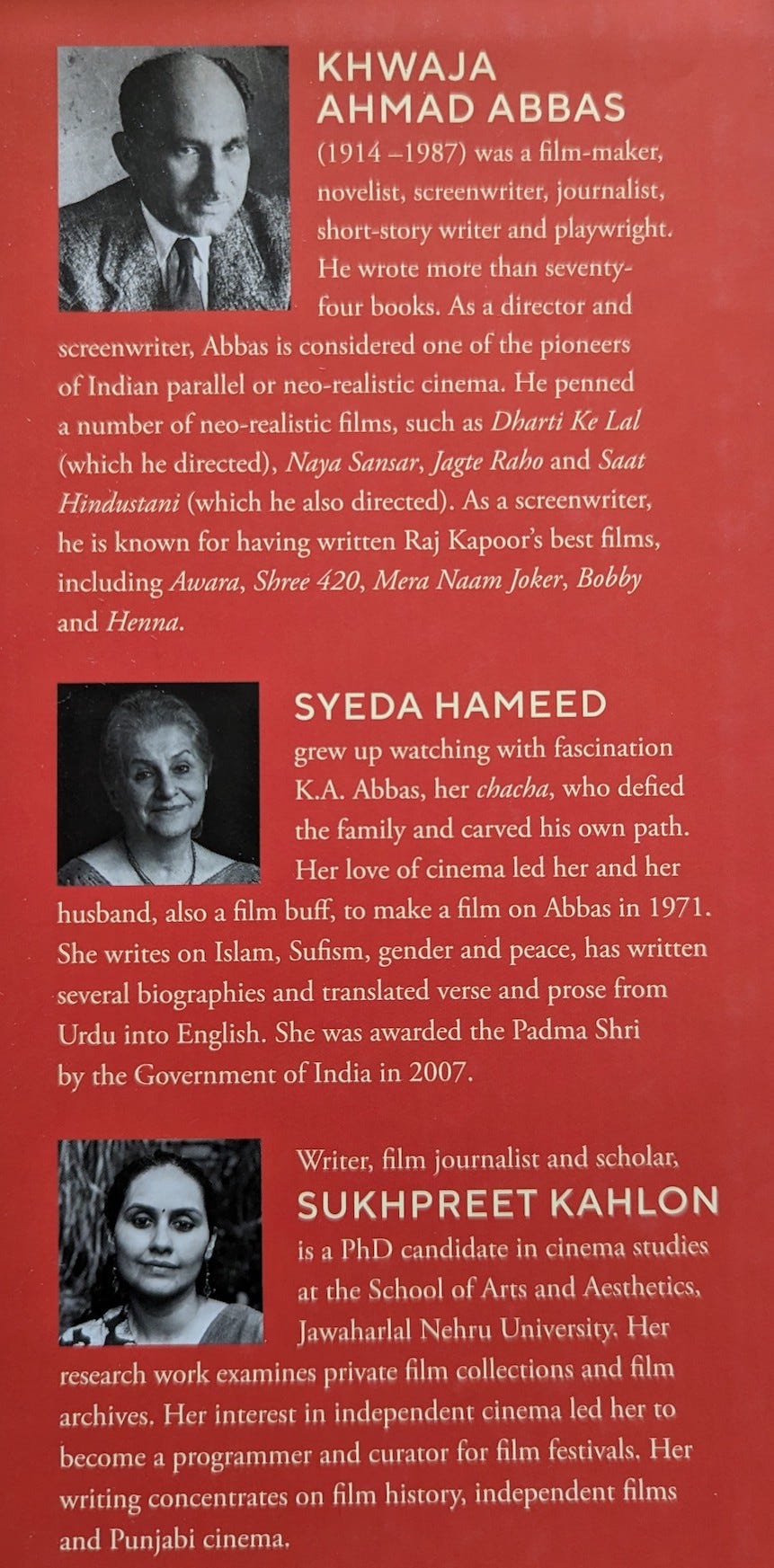

Sone Chandi Ke Buth, or Idols of Gold and Silver, has been translated by Syeda Hamid and Sukhpreet Kahlon, from their “tattered…dirty purple” copy. In the preface they point out an incredible fact about the man, which is that he wrote 74 books (in a lifetime of 73 years) consisting largely of the 3000 pieces of journalese written for Blitz magazine across 46 years. This was in addition to nearly 40 films that he wrote for and often directed.

This was a man who had found his life’s purpose in truly divine fashion and who pursued it quite like a prize horse in a race. And why horse and not jockey? Because the gentleman Abbas would appear to be designed to run, but wasn’t given to competitiveness. He believed that the purpose of his pen and his art was to uplift and encourage, and not to build distractions and self-aggrandise.

What then are the reasons I feel this book calls out to Indian cinema lovers? There are three.

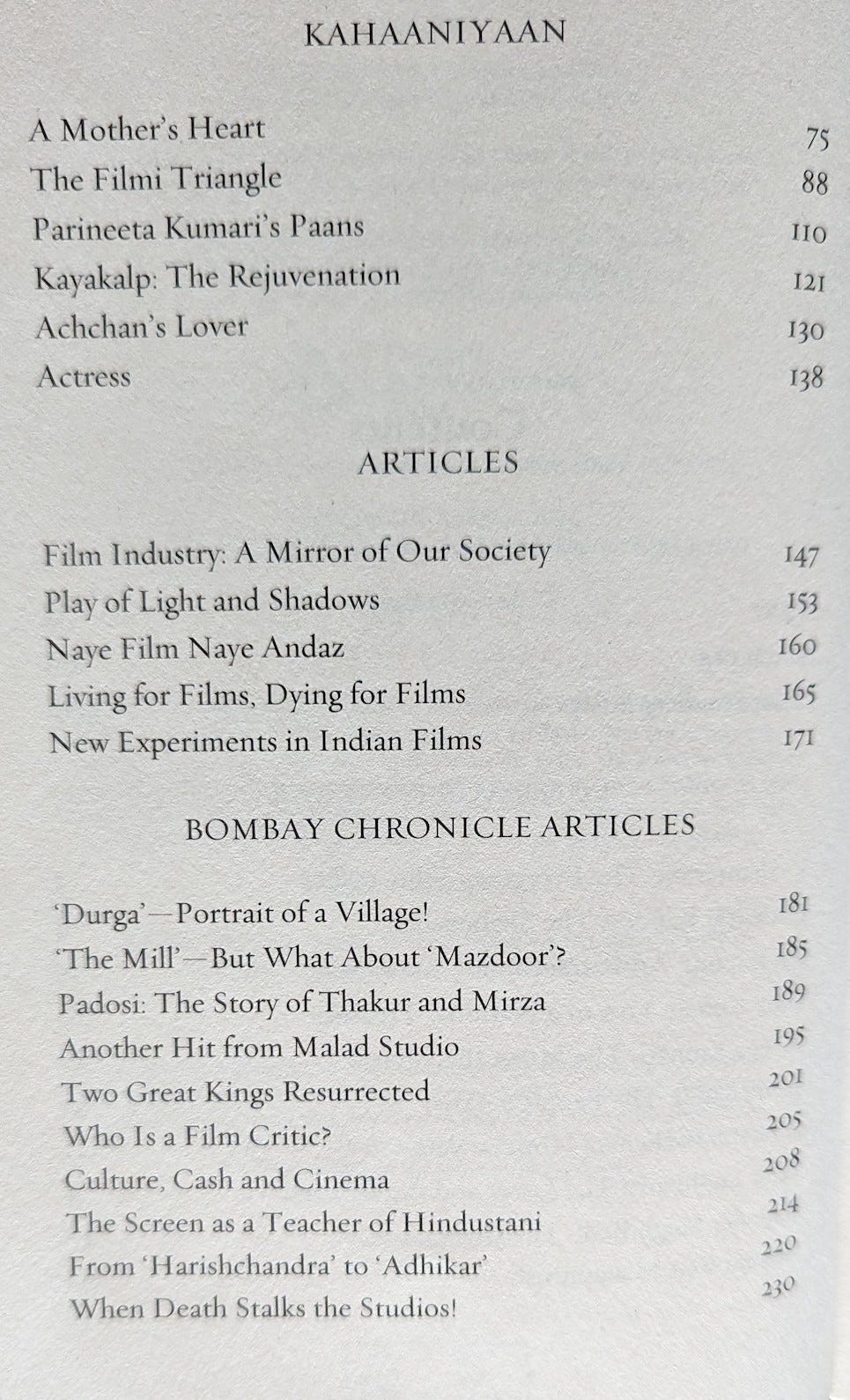

First, this book itself is a historical artefact. While not much can be found in the translation about when the original was published, the essays themselves range from the 1940s to the 1970s. As a result, one can suddenly be surprised to hear that there was a time when two hundred thousand (two lakh) rupees was a big budget to make a film. A wonderful essay ‘From Harishchandra to Adhikar’ charts the first quarter-century of Indian cinema (1913–1939) as it takes a broad look at all regional achievements in the art form. As an insider and close observer, Abbas also brings out the people who make up the industry. There are humanising pen sketches of towering figures like Meena Kumari and Prithviraj Kapoor, as well as a look at the forms of hierarchy that unnecessarily percolated into the crew. As a committed socialist, Abbas was against these proxy class divisions and his essay on the welfare of stunt artists brings to fore the respect he directed towards all members of the industry.

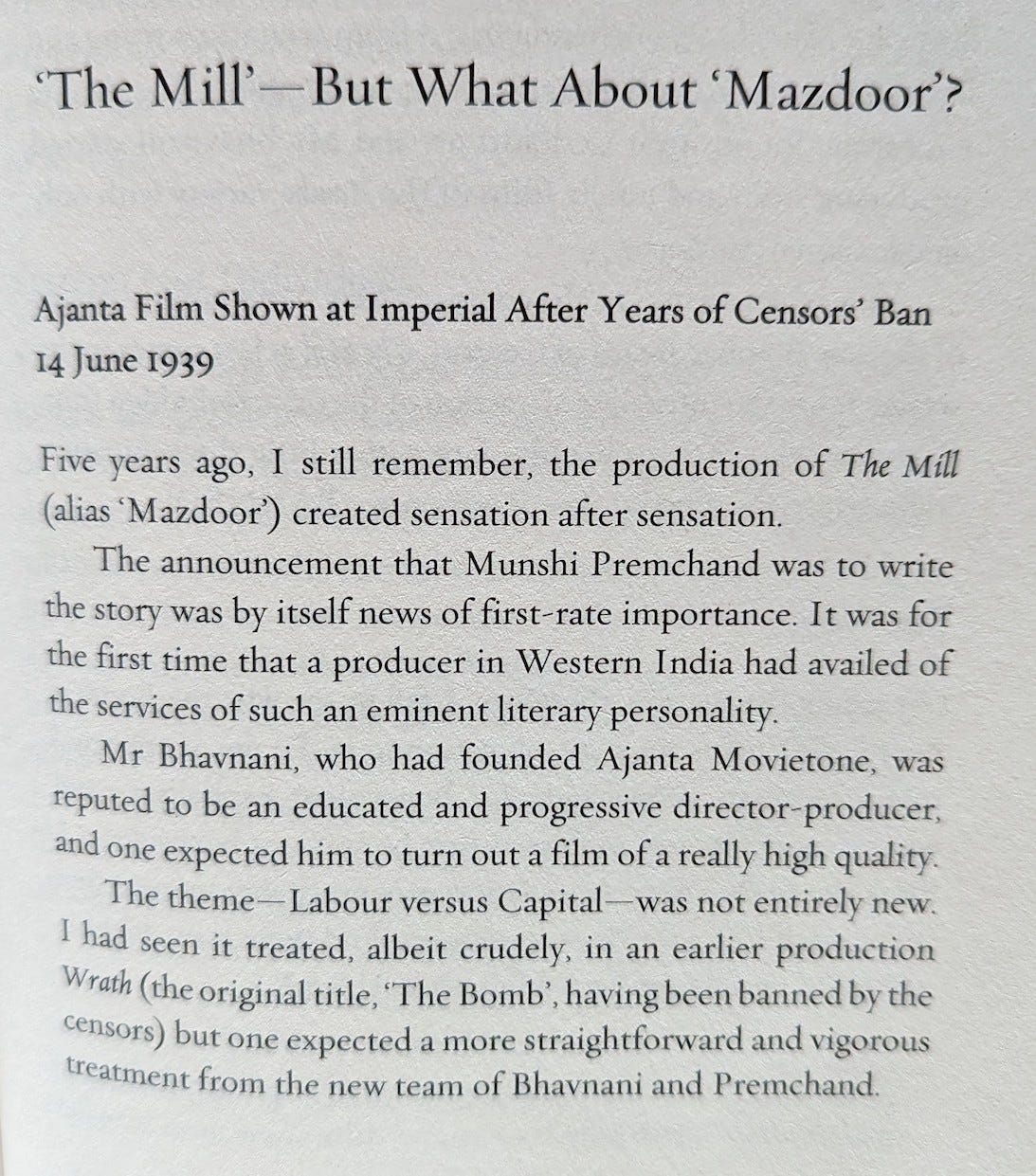

Second, this book is a good study for film critics and film journalists. In an era where reviews are only a couple of hundred words and rise only to the most superficial levels of analyses, Abbas takes us back to an era of purposeful writing. His film essays, written for the Bombay Chronicle, are deep explorations, and mix praise and criticism to bring out complexity. He was certainly bold in the manner that he called out the excesses of the industry, even criticising Dilip Kapoor, a man with an outsize presence in cinema. In ‘Durga — Portrait of a Village’, Abbas reviews the 1939 film featuring Devika Rani, and takes time to look at three separate characters and what they represent to the audience, before condemning a tame ending that did not do justice to the rest of the film. Even then, he goes on to give a final word of praise to the work done by Rani in elevating the titular character. Such is the balance that few critics, or even audience members, are capable of today.

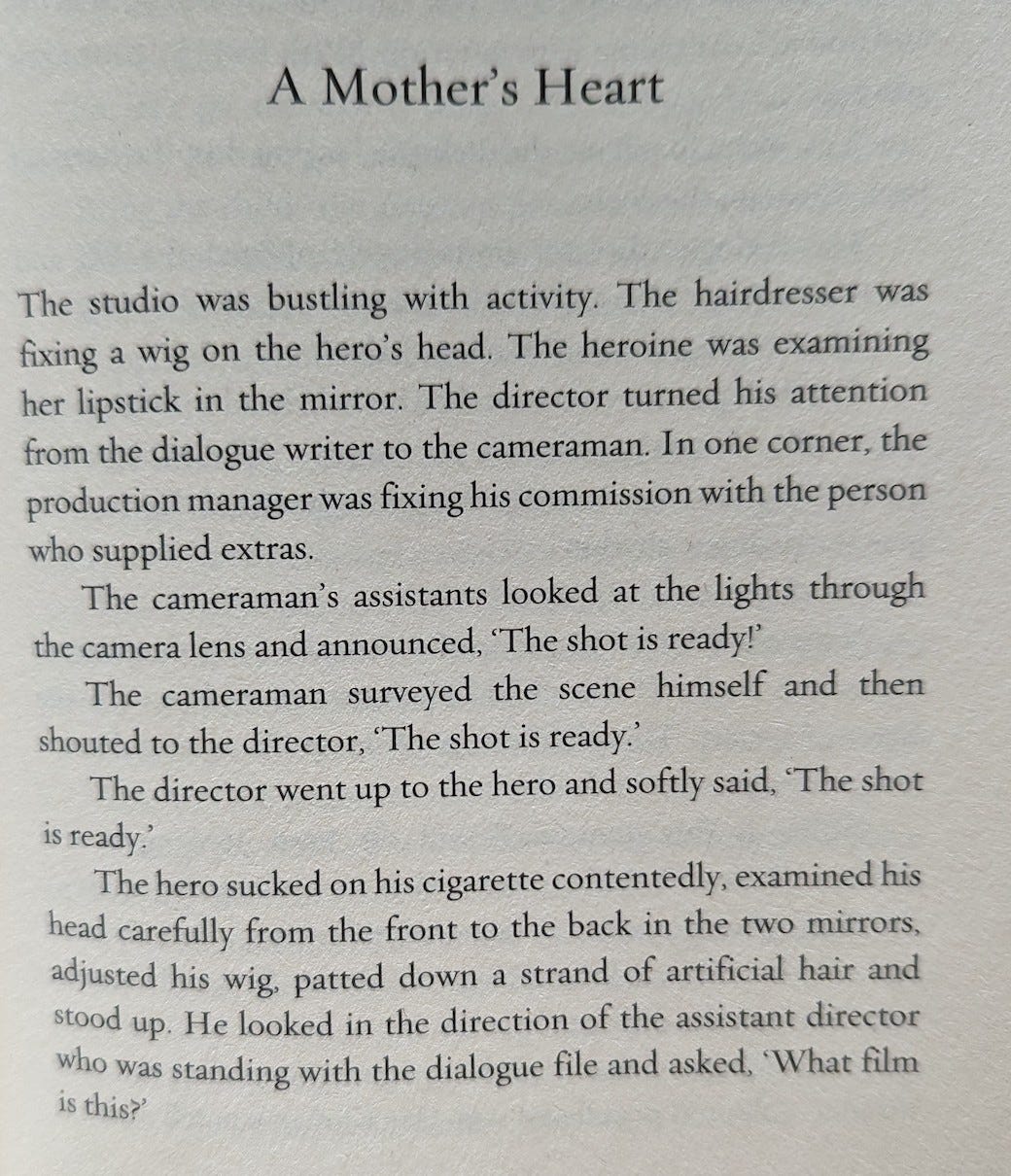

Finally, there is something for lovers of short stories. As a writer for cinema, Abbas certainly would have had many ideas that never made it to the big screen. A handful of them are presented in this book. The style will be familiar and welcome to those who admire the works of Manto, Chughtai, and Premchand. These are searing and tragic tales, but full of poetry. They are marked by pain but alleviated by heroism. What’s especially appealing is that all of the six short stories take place within the world of film-making, allowing us another chance to enter this liminal zone between reality and make-believe.

After giving you all these reasons, I feel I must also add that the book is not an entirely consistent read. I cannot tell you that every page is informative or eye-opening, or even interesting. The book works at the level of the woods and not the trees. A patient approach is required, and without that this book may not be a satisfying read. Given how much film-making and audience expectations have changed, this book, unfortunately, is a relic of a distant past and must be approached as such.

—

Thanks for reading my essay. Your interest gives me enormous motivation to keep on writing. If you have any comments I’d love to read and respond to them. And if you want to read some of my other works then head over to www.amazon.in/Sumit-Ray/ where you can see some of my fiction writing, and also a book of essays on Satyajit Ray’s entire fiction filmography (you can also read those at www.raybyray.in).

Leave a Reply