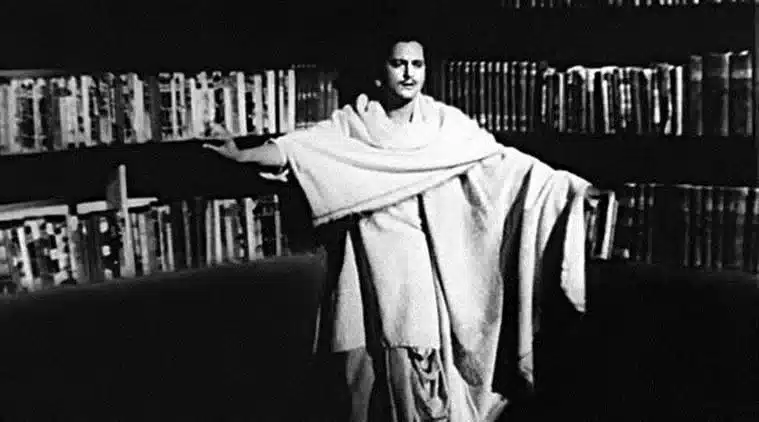

All of the times I’ve watched Guru Dutt’s magnificent film Pyaasa (1957) it has moved me to tears. To watch Vijay, the protagonist, struggle to make any progress with his obvious talent, to see the courage of Gulabo who puts her far greater problems aside to help someone else, to see the faithfulness of Abdul who never deserts his friend, these are all things that squeeze my heart out.

But there’s someone else whose pain I feel when I watch this film – and that is myself. Pyaasa is a film that I identify with far too much. I experience great catharsis from it in a way only struggling writers can do.

And there is a reason why this film about the struggle hits me much more than any other similarly-themed film can – in this film the writer is doing everything he can to achieve success and be happy and not opting for some melodramatic path of eternal suffering.

Vijay writes, he attends soirees, he tries to show his work to a publisher. In short, he does everything to achieve recognition and get some happiness for himself. He doesn’t like to be miserable, unlike many other fictional writers.

On the other side of this is Guru Dutt’s other film about an artiste, Kagaz Ke Phool (1959), where a successful film director called Suresh finds his entire career wiped out. His protégé, the actress Shanti, has the opposite trajectory, where she ascends to great heights while he plumbs his depths.

The artiste in this film is insufferable. He literally, yes literally, runs away from help. Shanti makes may attempts to give him new shots at success but he runs from her. His estranged daughter tries to find him but he hides from her. Happiness comes knocking at his door but Suresh’s ego, his misplaced sense of self-worth, keep him from embracing these opportunities.

Unfortunately, many aspiring and struggling artistes are likely to be seduced by the second character. This is because Suresh represents someone who can turn suffering rejection into an art and this seems to have an attraction for the young artistes ego.

Vijay, on the other hand, represents the uncaring cruelty of the world directed towards one man who cannot turn that into a piece of performance art. He doesn’t seem to have power over his own story in the same way Suresh does. And that’s frightening at the core.

But, when I see Vijay from Pyaasa, I see myself. I didn’t set out to be a moody writer who bites hands offering good-intentioned advice (yuck). But hard knocks have brought me to the stage where, like Vijay, I question the value of success altogether. Like him, I too keep repeating, “Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaaye toh kya hai…Jala do, jala do yeh duniya.”

“Even if you acquire this world, what then?…Burn down a world like this.”

Indeed, if you’ve trodden the path of Vijay, you will hate Suresh for spurning the helping hands of others. If you’ve struggled to get anybody to notice your talent and failed, you’ll know how insufferable Suresh’s problems are. And if you’ve found your Gulabo, you’ll kick Suresh in the shin for running away from Shanti.

Neither the artiste nor the public should romanticise the struggle to unhealthy extents. Give water to those who are thirsty, don’t pour that water on paper flowers.